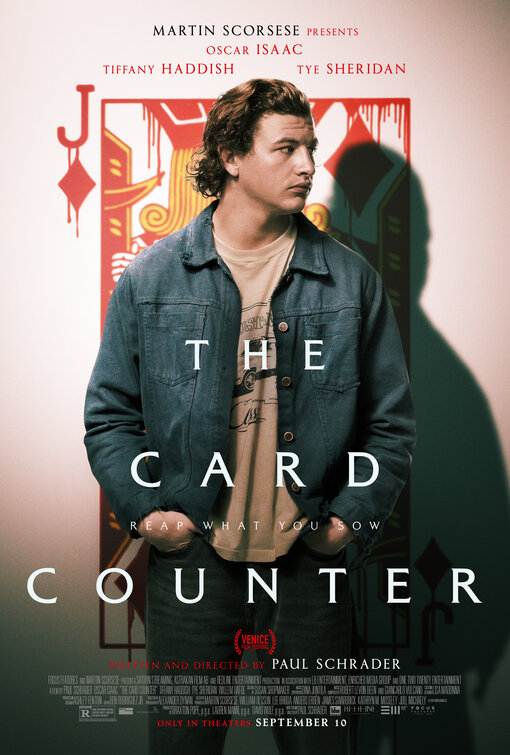

His spartan existence on the casino trail is shattered when he is approached by Cirk, a vulnerable and angry young man seeking help to execute his plan for revenge on a military colonel. William Tell just wants to play cards. The Card Counter (2021) Reap what you sow.

His latest film, then, is where you should go to find out what’s on his mind. They even mandated a freeze on his posting for the time being. Schrader’s additions to the cinematic canon are nothing short of legendary, but his Facebook output—stray thoughts on everything from classic films to, uh, the difficulty of not touching beautiful women in his employ—has caused concern for Focus Features, the studio distributing The Card Counter.

He’s a strange man with even stranger neuroses. He also likes to strip these motel rooms bare and wrap all their furniture in sheets and twine, turning them into self-made prison cells of sheer austerity. He keeps a low profile, quitting when his winnings are modest and spending his nights in cheap motel rooms. READ ALSO: Review: Rebecca Hall lifts ‘The Night House’The film stars Oscar Isaac as the cheekily named William Tell, a career gambler who games poker and blackjack tables across the country. Told with Schrader's trademark cinematic intensity, the revenge thriller tells the story of an ex-military interrogator turned.

Instead, the cinematography is lurid, dark, and almost voyeuristic, lurking around corners to show us what no one should see. Torture isn’t something to meditate on. The Card Counter is concerned with the spiritual, but it’s too buried in the muck of human vice to fit a transcendental approach. It’s a style that lends itself well to spiritual films. His previous film First Reformed was shot in transcendental style—a method of filmmaking that Schrader literally wrote the book on—which uses lengthy, motionless, meditative shots to stress the monotony of life, making it all the more powerful when a transcendent force breaks through the gloom. In other words, he tortured people for a government that was lying to his face.It’s a raw, difficult subject, and Schrader wisely switches up his style to honor that.

Torture begets torture.How does gambling fit into this? Metaphorically, mostly. And hell is always close by: at the peak of a magnificent performance, Isaac describes the sights, sounds, and smells of the Abu Ghraib operation, and you can feel the weeping and gnashing of teeth in his shuddering body you can see it in his dead eyes. Featuring original compositions from Black Rebel Motorcycle Club vocalist Robert Been, the score is swirling with deep sighs, heavy bass, and the repetition of haunting phrases.

Isaac’s chemistry with Tiffany Haddish, who plays a gambling financier, keeps the games from wilting as well. Paramount to the allegory is the relationship between “tilting”—in poker terms, losing your mental balance and slipping up—and the debt it incurs.Schrader’s more interested in the metaphorical potential of card games than in card games themselves, so the lengths of time in which poker games play out are the film’s least interesting—though they are spiced up by dark humor. Some metaphors are more obvious than others, like the poker player who dresses in American flag apparel and wins every game, but others are more carefully coded.

Thus, the country was set up at an angle, giving those at the top the protection and power of the house. Someone has to lose it—their mind, their money, or their life—for someone else to profit. To The Card Counter, there’s no American experiment without tilt. Whether it’s out-of-touch dialogue (“have you heard of Google Earth?”) or lower-key scenes going on a little long, The Card Counter isn’t as tight as Schrader’s best films.But it’s still potent—pungent, really, with the stench of a country that plays games with people’s lives. Interruptions in tone are more common here than in Schrader’s other work.

And maybe they can put the flames behind them. Hell isn’t where the bad men go—it’s where they come from. We’re products of our environment, not fallen creations. But as with Schrader’s First Reformed, it implies a glimmer of hope, one with theological import: if we inherit our debt, our sin, not from Adam but from America, then our souls aren’t the problem.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)